10.4 CHANGING DEFINITIONS OF HEALTH AND AGING

The twentieth century experienced unprecedented increases in life and health span. In just 100 years, life expectancy from birth has doubled, and infectious diseases, diseases that killed the majority of people prior to 1900, now cause less than 1% of mortality in individuals over the age of 65 years. Today, management of chronic disease, whether through prevention or drug therapy, allows the older population to enjoy life well into their 9th and 10th decades. Younger populations can expect even greater life and health spans as we enter into the era of precision medicine (see Box 2.2).

The increased life span and extended good health of the older population are changing how individuals and society view the process of growing old. Individuals need to consider that their nonworking life, conventionally known as retirement, may be the same or of greater length than their working life. The possibility of good health into old age offers the individual an opportunity to remain fully engaged in life, with only limited functional loss, up until a short period prior to death. The majority of individuals in the older population, a population historically marginalized relative to the younger population, are remaining productive and vital members of society after retirement. The youth-oriented social paradigm that has shaped the cultures of the world for millennia can no longer be sustained.

In this section and continuing into the next chapter, we explore some of the changes that are beginning to take place in a society where both the young and old populations have equal value. We begin by exploring the changing definition of health as we move into an era where medical care focuses on the uniqueness of each individual, precision medicine. Then, we continue our discussion of what it means to be physically healthy by focusing on the concept of successful aging. In Chapter 11, we discuss how extending the healthy life span will impact society and culture.

World Health Organization's definition of health includes subjective measure of well-being and prospect of complete health

Defining health has great value to individuals and populations. Health definitions help to guide physicians in their conversations with patients on how to achieve good health. Public health officials use health definitions as markers with which to measure the health of a population. Since 1948, the World Health Organization (WHO) has set the standard for a definition of health as “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.” The development of the WHO definition of health was, in large part, a response to the state of treatments for disease in 1948. At that time, the fields of human biology and medicine were transitioning from a focus on acute lethal diseases to one that concentrated more on treating and curing noncommunicable, chronic diseases. Treating noncommunicable, chronic disease with drugs was a relatively new phenomenon in 1948, as the pharmaceutical industry as we think of it today was in its infancy (pharmaceuticals companies were born in the 1930s and 1940s). The pharmaceutical industry had only just begun to provide drugs extending the life span of individuals with chronic disease. Since individuals were now living with chronic disease, health could no longer be objectified merely as the absence of disease. Health was becoming a subjective term that had to include a measure of personal satisfaction with life despite having a disease, that is, well-being.

The WHO definition of health was visionary for its time (1948), because it encouraged the physician and patient to consider that a state of complete health was possible. The potential for attaining complete health was fostered, in large part, by the overwhelming success of curing many communicable diseases that occurred during the first four decades of the twentienth century. The medical field was optimistic in 1948 that curing noncommunicable disease was also possible in the decades ahead. By including the word complete in their definition of health, the WHO was challenging the biomedical field to develop cures for chronic diseases.

Individual ability to adapt to health circumstances will define health in era of precision medicine

The optimism of the 1948 WHO definition of health was premature, as the ideal of complete health has not been realized. One can hardly fault the men and women who crafted this definition for believing that complete health was possible. They could not have predicted that the etiology of noncommunicable disease would be so complex that 70 years later most chronic diseases would not have cures. It is also unlikely they would have envisioned a time in which 20% of the population in economically developed countries would be over the age of 65, a population in which 100% of the individuals have time-dependent functional loss, chronic disease, or both. As such, 60–80 million people in the United States (585 million worldwide) are unhealthy according to the WHO definition simply by virtue of being old.

Management rather than cure of chronic disease currently defines the status of medicine in economically developed countries. The WHO definition of health with its emphasis on complete health has become outdated and inconsistent with the realities of modern medical care. Moreover, the one-size-fits-all approach to health definitions will have little meaning as we enter the era of precision medicine. As you learned in Chapter 2 (Box 2.2), a major goal of the Precision Medicine Initiative is the development of different disease taxonomy, one based largely on each individual's unique expression of a pathology. If we are to define disease as being unique to each person, should we not also define the health of an individual on a case-by-case basis? Most experts agree that the answer to this question is yes. Together, the growing aged population and the coming of precision medicine require that the definition of health include language recognizing the right of the individual to define his or her own health status.

Reformulation of the definition of health must be dynamic enough to match a changing view of disease as precision medicine becomes more entrenched in medical care. Rather than expecting complete health, a precision medicine definition of health will, most likely, focus on one's ability to adapt and manage any limitations to daily living. Adaptation to life's inevitable hardships, including any residual effect of a disease or disability, takes into account the distinctive ability of our species to cope with adversity and restore one's sense of happiness and well-being. Restoration of a sense of well-being despite physical limitations has become particularly relevant in this age of extended life span. As expressed numerous times in this text, every individual who lives beyond the age of reproduction will experience time-dependent functional loss, chronic disease, or both. Those who accept functional loss as a part of life and adapt to its limitations will be viewed as healthy. To this end, we now explore the concept of successful aging, a definition of healthy aging whose foundation lies in adaptation to functional loss and personal responsibility for limiting the effects of aging.

Growing old was once viewed as time of disease, disability, and disengagement from life

Research in biogerontology was once guided, almost exclusively, by a paradigm maintaining that normal or usual aging includes disease, disability, and disengagement. This paradigm was established at a time when the population of older individuals was less than 4% and management of chronic disease was minimal (see previous discussion). That is, disease, disability, and disengagement were common among the older population. In fact, healthy aging was seen as so rare that individuals falling outside the accepted norm for usual aging were considered genetic anomalies. As an example, older individuals who exercised regularly were not included in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging during its first 30 years, because a sedentary lifestyle was seen as normal aging.

Usual aging as a time of disease, disability, and disengagement began to be questioned in the early 1980s when epidemiological research and public health vital statistics were describing a growing population of older individuals maintaining health and an active engagement in life. Extended life span and having a low risk for chronic disease were correlating well with abstinence from tobacco, moderation in alcohol intake, regular exercise, and healthy dietary choices. It appeared that the older population was becoming heterogenetic, and the model of aging as disease, disability, and disengagement was becoming untenable.

Advances in biomedicine during the 1980s were extending the life span of individuals with chronic disease, individuals who in previous decades would have died. Surgical techniques and drug therapies were allowing individuals with chronic diseases, for example, heart disease, to maintain otherwise healthy and fully engaged lives. Clearly, time-dependent chronic disease was not the sole factor in defining health in the older individual. This was also a time when human longitudinal investigations studying biological aging were suggesting that the concept of “normal aging” had no meaning. These studies were reporting that the rate of aging was random with respect to its timing and physiological system affected (see Chapter 2, section titled, “Longitudinal studies observe changes in single individual over time”). The long-held view that the rate of aging was the result of an ordered biological mechanism was giving way to the current understanding that the rate of aging was highly individualized and modifiable.

Heterogeneity of function within older population led to concept of successful aging

Strong circumstantial evidence was accumulating to suggest that lifestyle choices such as abstinence from tobacco and physical exercise slowed the rate of aging. Also accumulating was ample evidence that the older population was significantly heterogenic in regard to physical and mental function. Within the overall older population were subpopulations that were seen as high functioning and other subpopulations that were low functioning. The heterogenic nature of the older population implied that disease and disability did not have to be, as the majority of gerontology research had suggested, the normal or usual outcome to growing old. It was within these historical settings that many researchers began to ask the following questions: Could the rate of aging be slowed and development of chronic disease be delayed in the older individual? If so, what were the factors that led to healthy aging?

In 1987, researchers John W. Rowe, a physician, and Robert L. Kahn, a social psychologist, published a paper in the highly esteemed journal Science that would ultimately change the primary research model used in gerontological research. These two researchers suggested that the research model accepting disease and disability as usual aging was flawed. The limitation to this model lied, in large part, in the general acceptance of a biologically determined normal or usual aging. Rowe

and Kahn saw that “usual aging” had been established imprecisely through group averages in studies comparing young versus older populations. Group averages were ignoring the extensive and much greater heterogeneity that existed in the older versus younger populations (see Chapter 2, Figure 2.6). Rowe and Kahn suggested that a more appropriate model of aging research was to focus on the factors accounting for the heterogeneity of function within the older population. They wrote:

“Research on aging has also emphasized differences between age groups. The substantial heterogeneity within age groups has been either ignored or attributed to differences in genetic endowment. That perspective neglects the important impact of extrinsic factors and the interaction between psychosocial and physiologic variables.” (Rowe and Kahn, 1987)

Important to Rowe and Kahn's focus on heterogeneity within the aging population was the subpopulation of older adults that included “older persons with minimal physiological loss, or none at all, when compared to the average of their younger counterparts” (Rowe and Kahn, 1987). They argued that this healthy population of older individuals demonstrated that disease and disability were not inevitable outcomes of aging. Rather, older individuals demonstrating usual aging, that is, the declining function defined by group means, were capable of improving physical function. This led Rowe and Kahn to introduce the concept of successful aging. Their choice of the word successful was meant to convey that aging well was a conscious and deliberate decision on the part of the individual. Again, from Rowe and Kahn,

“Our concept of success connotes more than a happy outcome; it implies achievement rather than mere good luck. …. To succeed in something requires more than falling into it; it means having desired it, planned it and worked for it. All these factors are critical to our view of aging which, even in this era of human genetics, we regard as largely under the control of the individuals.” (Rowe and Kahn, 1998)

Successful aging includes physical, behavioral, and social components

Rowe and Kahn were researchers and not simply theorists espousing a position to be tested. Their thoughts on successful aging were based on results from a longitudinal investigation they had designed and carried out in collaboration with 16 other research groups. Rowe's and Kahn's intent was to establish an interdisciplinary research collaboration that included a wide range of perspectives, including expertise in the biomedical, behavioral, and social aspects of gerontology. To this end, this research group periodically measured a wide variety of physical, biological, and behavioral variables in more than a thousand, 70- to 79-year-old adult individuals over a 7- to 10-year period. Their baseline test confirmed the findings of previous cross-sectional and longitudinal investigations that function within an older population was extremely varied. Some individuals were performing at levels expected in individuals aged 20–30 years younger. Others, of identical ages, showed significant declines in both physical and cognitive measures.

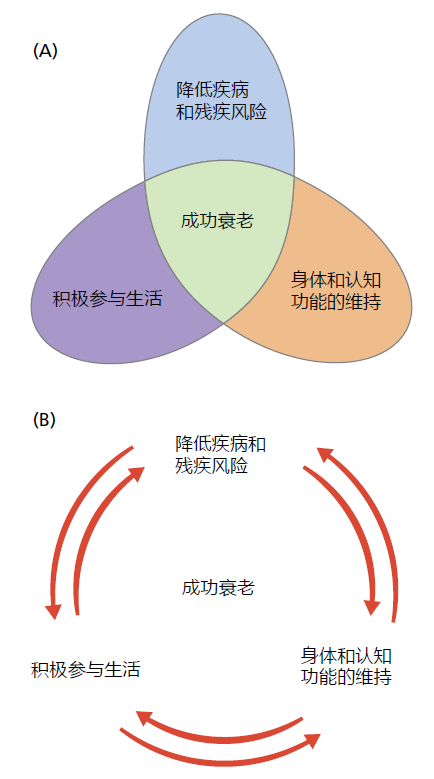

Analysis of the baseline measurements from individuals participating in the Rowe and Kahn study resulted in the establishment of three groups: high, medium, and low functioning older adults. The remaining years of the longitudinal investigation were focused on identifying the factors that account for the heterogeneity among the three different functional groups. Based on the data collected over the 7- to 10-year period, Rowe and Kahn established a now widely published three-component model leading to successful aging (Figure 10.11A and B). From Rowe and Kahn,

“We define successful aging as including three main components: low probability of disease and disease-related disability, high cognitive and physical functional capacity, and active engagement with life. All three terms are relative and the relationship among them . . . is to some extent hierarchical . . . successful aging is more than absence of disease, important though that is, and more than the maintenance of functional capacities, important as it is. Both are important components of successful aging, but it is their combination with active engagement with life that represents the concept of successful aging most fully.” (Rowe and Kahn, 1998)

Figure 10.11 Rowe's and Kahn's three-component model of successful aging. (A) Through this illustration, Rowe and Kahn emphasized that no single component was more important than the other in creating successful aging. That is, the combination of the three components was the essential factor for successful aging. (B) Interdependence and hierarchical nature of successful aging. For example, an active engagement with life can lead to maintenance of physical and cognitive function that, in turn, can lead to reduced risk of disease and disability. Or, a reduced risk of disease and disability can lead to maintenance of physical and cognitive function that … and so on. (A, adapted from Rowe and Kahn, Successful Aging, 1998.)

Successful aging received significant criticism for placing too much focus on an “ideal” of health rather than the realities of life. Such criticism points out that a large segment of the aging population does not have sufficient access to the financial, physical, and mental health resources necessary to obtain successful aging. Moreover, some critics suggest that the model of successful aging fails to consider that success is a subjective term having a wide range of definitions. Research has consistently shown that older individuals with severe disabilities and long-standing chronic disease are just as satisfied with their lives as are those who meet the criteria for successful aging. Most agree that we must guard against a model of healthy/successful aging that neglects those less fortunate and does not provide room for a personal definition of success in later life.

Supporters of the successful aging research paradigm have argued that it was never intended to be used as stand-alone criteria for determining who was or was not aging successfully. Rather, successful aging was a term used by Rowe and Khan in 1987 to challenge the widely accepted research paradigm of aging as a time of disability, disease, and disengagement from life. The field of biogerontology in 1987 accepted, for the most part, the proposition that aging was under genetic control and had a definable set of phenotypes. It would be a decade after the publication

of Rowe and Kahn's original paper on successful aging that evolutionary biogerontologists would conclusively show that genes were not selected for aging; decline in function was not a deterministic biological program. We now know that environmental factors, including lifestyle choices, are the primary factors accounting for each individual's unique phenotype of aging. As such, the way and rate at which we age are malleable and under personal control.