11.2 SOCIAL AND CULTURAL CHANGE IN AN AGING SOCIETY

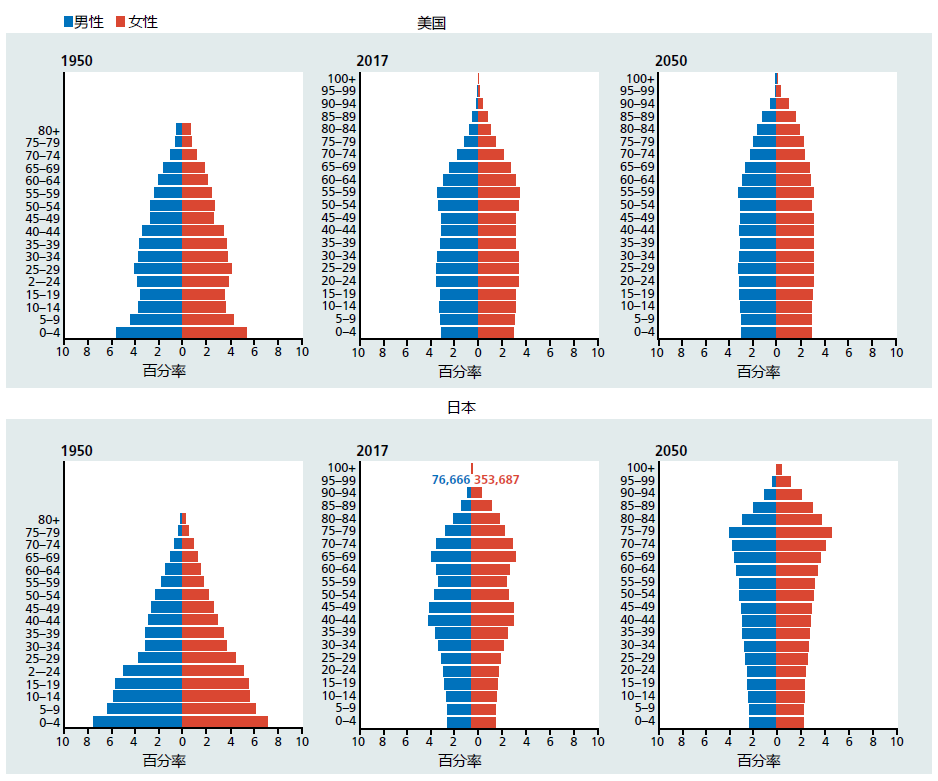

The cultures of today have been shaped by the needs of the young, and rightfully so. For millennia before 1900, people lived in a young society where the average age of death was 35–45 years and only 2%–4% of the population made it past the age of 65. Cultures had little choice but to prioritize their resources toward the young and develop society norms around the youth. However, adherence to a society's norms that emphasize exclusively the young is no longer tenable. Figure 11.7 shows that the age groups within the age structure have become equal. That is, the young population no longer dominates the age structure. Ninety percent of all people alive today will see their 70th birthday, and 50% will make it to 80 years. While we must continue to nurture the young so that they take their position as future leaders in society, the wants, needs, and desires of the older population must also be considered. The shift from an exclusively young-oriented culture to one that includes all age groups will profoundly affect the basic structure and norms of society. Here, we briefly consider what bioethicists, sociologists, biologists, and other experts are saying about this new social order.

Figure 11.7 Age-structure in United States and Japan for the years 1950, 2017, and 2050 (projected). For both Japan and the United States, the age of the population has shifted from one in which the younger age group are the greatest (1950), to one in which the older age group are equal to the younger (2017). This trend will continue for the foreseeable future (2050). The projected (2050) age structure of Japan reflects what may happen to many economically developed countries. That is, an older age group, here 75–79, has the greatest percentage of the population within the age structure. (From PopulationPyramid.net, Martin De Wulf; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/us/.)

The biogerontologist has a significant role to play in shaping the society of the future. Recall what you read in the first few pages of the first chapter of this book: “Biogerontological research that leads to improved health and extended life must be reconciled with the fact that aging will occur no matter how successful the remedy for a specific age-related dysfunction, and that death will be the endpoint for the individual. Thus, biogerontologists are required not only to be experts in their particular field but also to be active participants in discussions on the psychological, social, and economic consequences of improved health and well-being in the older population.” The purpose in this section is to give you a frame of reference for entering this discussion, not to provide you with answers about how societies will change.

Healthier and longer life may modify perception of personal achievement and progressive society

Many view the prospect of an extended life- and healthspan with great optimism and see it as a possibility for new opportunities. With the expectation of a longer and healthier life, individuals are more likely to engage in projects or new ventures that are beyond reach in a shorter life span that requires a more careful prioritizing of goals. For example, mistakes may simply encourage a person to choose a new career that fits more closely with his or her personality and aspirations. Such a move could easily be undertaken at age 70 or 80 if you have the prospect of living another 30 to 40 years. The expectation of a 100- to 120-year healthy life span may make the youth more willing to experiment with risky vocations and avocations, as they will have time to make several attempts at the same venture or start an entirely new one. Since risk is the cornerstone of progress and discovery, society can only benefit.

Other bioethicists take a more pessimistic view. They theorize that an extended youth could remove a sense of urgency, resulting in decreased commitment to goals and aspirations. If individuals know they have a chance for a “redo,” they may be less inclined to commit to any particular venture. The “stick-to-it” attitude might give way to prematurely abandoning one's ventures. The “redo” then becomes the way of life. Goals, aspirations, and the value of personal achievement could simply lose their meaning, leading us to become a society of the status quo rather than progress.

Extended longevity and health may change responsibility for renewal of species

An extended life span and healthspan could also disrupt individuals' sense of responsibility for renewing the species. Proponents of this position point to the fact that the increase in life span during the twentieth century was accompanied by a decrease in birth rate and a trend toward starting reproduction later in life. The sense of urgency about having children is being replaced by the feeling that it can wait. Many believe that youth should be spent living the “good life” without children. However, many couples find that the “good life” is too difficult to give up, and so they do not to reproduce at all. In addition, those delaying reproduction may find that later in life they may want children, but their reproductive system might not cooperate. Both men and women become less fertile as they approach the end of their reproductive period. Moreover, for women, the increase in birth defects after the age of 35 may seem too great a risk to consider having babies. A reduction in the birth rate will simply reflect biology.

Others believe that birth rate has little to do with life span. Rather, birth rates are more tied to the economic prosperity that comes with the shift from agrarian to industrial societies; longer lives are simply one of many positive outcomes of the industrial society. In an agrarian society, much like all societies before the start of the twentieth century, children are viewed as an asset because they add value to the family by providing labor for work on the land. However, in industrial societies children are dependents, costing the family resources. Historically, agrarian societies could expect one in four of their children to die before reaching the age of reproduction, so couples often had many children as a hedge against the loss of labor. Today, in developed countries, it is more rare to lose a child to disease or accident. Life in an industrial society, together with the gains in health care for children, means that couples have fewer children.

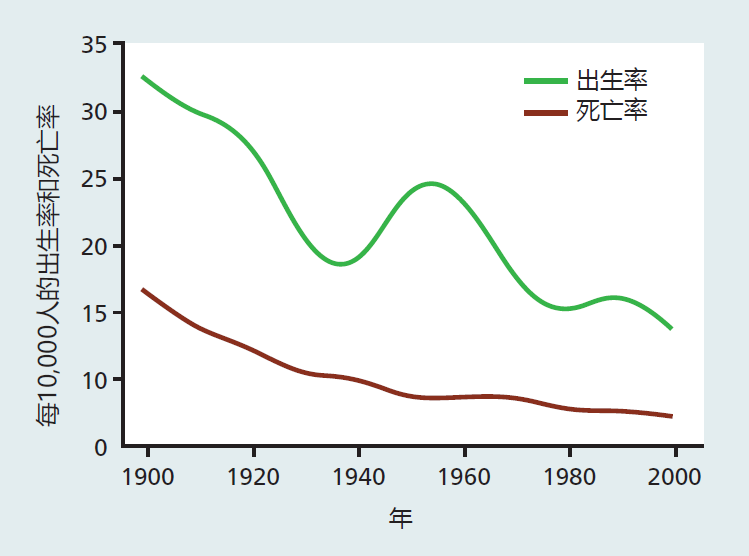

The declining birth rate in the twenty-first century may simply reflect the natural evolution of populations living in environmentally stable conditions, rather than a decreased desire to renew the species. As you learned in Chapter 3, the number of live births is significantly lower for populations living in environmentally stable conditions than for populations with more variable environmental conditions. Most economically developed countries are characterized by a vast majority of the population having sufficient food, housing, clothing, health care, and other basic needs of life—that is, a stable environment. There is no need to add children to the family as insurance to offset future losses of family members due to environmental hazards. Such a society becomes stable, with birth rates approaching death rates (Figure 11.8). The stability of this population will most likely continue, even with extended youth and longevity.

Figure 11.8 Birth and death rates in the United States, 1900–2015. (Death rates from Chong Y et al. 2015. Deaths in the United States, 1900–2013. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; Birth rates from Martin JA et al. 2017. Births: Final Data for 2015. National Vital Statistics Report; vol 66, no 1. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.)

The reproductive abilities of individuals with extended youth and life span has also been called into question. As you have learned throughout this text, reproduction and longevity are tightly coupled. A change in longevity implies a change in reproductive ability and reproductive life span. This is all the more possible given that extended youth and a longer life will most likely be the result of interventions taking place early in life, during development (see Chapters 3 and 5). In addition, solutions to the problems of decreased fertility and birth defects are being investigated much more vigorously than ways of extending a healthier life span. One can expect advances in reproductive medicine to at least parallel advances in other areas of health.

Low birth rates and extended longevity may alter current life cycle of generations

The structure of families and society is established around a life cycle in which each generation expects to play a well-defined role. For most of history, and for modern society, the life cycle of the family has included three generations: children, parents, and grandparents. Children are nurtured into adulthood by relatively young parents. Parents are expected to be the primary caregivers and to teach this new generation the basic tools needed for an independent adult life. Grandparents are often not as involved in the caregiving of the new generation, playing only a supporting role in the lives of their grandchildren—babysitting, providing gifts, and so on. Grandparents' main role in the family structure centers more on passing their wisdom to their children (the parents of the new generation). The path of knowledge and wisdom transfer in this three-generation life cycle, grandparents to parents to children, is short enough that family traditions are passed on without significant alteration. The family gains its own identity, and the individuals within the family feel a sense of belonging.

The three-generation structure of the family can be used as a metaphor for society in general, with each generation having a particular role. The new generation of children is expected to participate in a training and education system that prepares them for their eventual role as productive citizens of society—similar to the parent-child relationship. When children transition to adults and enter the workforce, they must take their place at the bottom of the ladder and work their way into positions of authority and wisdom. As in the grandparents' role in the family structure, the functions of society are imparted by the older generation at the top of the ladder, those who have been through the process themselves. The three-generation structure of society also provides the individual with incentives to achieve and to move society forward in a positive direction. We learn early on that success in school will lead to success at work and in the community, which will lead to authority, power, and wealth.

The three-generation life cycle in the family and in society has developed based on a 60- to 80-year life span. In this model, the child can expect to progress to the parent, and the parent can expect to progress to the grandparent. The expected and orderly progression occurs because the grandparent or older generation is removed by death or infirmity, leaving room at the “top.” But what if extended youth and a longer life delay death and infirmity so that the “wisdom” positions in the family and in the top tiers of society become overcrowded? Imagine, for example, a family structure in a world where average life span is 110 years. The family of today would give way to a family that includes healthy and active great-grandparents, great-great-grandparents, and possibly great-great-great-grandparents. Thus, the wisdom position in the family grows from 4 grandparents to as many as 32 great-great-great-grandparents. The succession of family tradition and identity made possible by the three-generation model weakens due to the sheer bulk of input from the wisdom positions. There are those that suggest the loss of family identity will lead to the loss of individuals' connection to the past and will challenge individuals' views of their own place in the world.

Some predict that as birth and death rates approach equilibrium (Figure 11.8)—a trend that will undoubtedly continue—total population size will stagnate, economic growth will become sluggish, and job creation will slow down. Moreover, with the extended youth and health of the older population, fewer people in top-tier jobs will likely retire. A reduction in jobs at the top means slower advancement for those on the way up and a shortage of jobs for the younger generation moving from training to work. Our concept of hard work leading to success will be challenged. Given all of this, we will need to redefine what constitutes a productive member of society. Many experts suggest that this redefinition will be slow and will take a considerable toll on the first generation to deal with this new economic structure.