10.4 LOOKING TOWARD THE FUTURE: THE IMPLICATIONS OF MODULATING AGING AND 寿命

Biogerontology underwent an important transition during the late 1990s. Identification of the fundamental causes of aging and longevity shifted the emphasis of research from observational studies focused on defining aging to experimental investigations of how the rate of aging can be slowed and longevity extended. As we have seen, low-calorie diets and increased physical activity are proven methods for slowing the rate of aging, but the population as a whole has had difficulty adopting such a strategy. This strongly suggests that more passive, medically centered interventions—taking a pill, undergoing gene therapy, and so on—will be needed to persuade people to take an active role in delaying aging.

At present, however, there is no credible scientific evidence supporting a medical intervention that slows, stops, or reverses human aging. Any suggestion to the contrary is either a misleading marketing technique used to sell a product or the claim of a fringe group expounding its own vision of reality. Nevertheless, the new biotechnologies being applied to research in biogerontology provide great hope that slowing the rate of aging and extending the average life span through medical interventions will be possible in the not too distant future. The precise number of years that will be added to current life expectancy is anybody's guess, but average life spans into the tenth, eleventh, and twelfth decades are often predicted by knowledgeable biogerontologists and demographers.

The increased life span and extended youth expected from the biotechnology revolution will take humanity into unknown territory, one that will profoundly change the basic structure of society. For the first time in history, society will have to make room for the wants, needs, and desires of a population that has moved well beyond the promises of youth on which society has traditionally been based. The outcomes from this new social order are unforeseeable. But the conversation about what our society might look like and the consequences of this new order has at least started. Here, we briefly consider that conversation and what bioethicists, sociologists, biologists, and other experts are saying about this new society. We focus primarily on what individuals' longer life will mean to the culture and structure of society.

The purpose here is to give you a frame of reference for entering this important discussion, not to provide you with answers about what society will be like. Recall what you read in the first few pages of the first chapter of this book: “Biogerontological research that leads to improved health and extended life must be reconciled with the fact that aging will occur no matter how successful the remedy for a specific age-related dysfunction and that death will be the endpoint for the individual.” Biogerontologists are required not only to be experts in their particular field but also to be active participants in the discussion on the psychological, social, and economic consequences of the improved health and well-being of the older population.

10.4.1 Extended youth and the compression of morbidity will characterize aging in the future

The quest for a long life, and its consequences, are as old as civilization. Greek mythology tells of the god Apollo granting Cumaean Sibyl one request in exchange for her virginity. She chose eternal life. Sibyl forgot, however, to include eternal youth in her request, and she spends eternity suffering the disabilities of old age. The mythology of ancient Greece reminds us that most people are unwilling to accept a long life without good health. Significant life extension must and will come with extended youth and relatively good health into old age.

Some have predicted that life extension will be analogous to the stretching of a rubber band. That is, all phases of biological life will be extended, including the period of increased morbidity that often precedes the end of life. Most biogerontologists whose research focuses on the future of aging disagree with this rubber-band analogy. Rather, they suggest that the increased morbidity at or near the end of life will last, at most, a few months—the same as it does now—or, more likely, a significantly shorter time. Thus, the percentage of the life span spent experiencing senescence-related morbidity will decline, a phenomenon known as the compression of morbidity.

With the promise of extended youth and the compression of morbidity, our discussion can focus more on the ethical and cultural issues of an aging society by eliminating, to a large degree, concerns about economic catastrophes resulting from overburdened health and social security systems. Total expenditures on health care are expected to rise with extended longevity (though some suggest that curing disease will lower expenditures on costly diagnostic and therapeutic procedures).

However, this rise in health care costs will result from the increase in overall population due to a larger aging cohort, rather than from the ill health of the oldest sector. The issue, then, becomes a political argument about how best to deal with health care costs, a discussion not unlike that taking place today. A similar consideration is the insolvency of the U.S. Social Security system that is likely to result if policies for participation (as outlined in Box 7.1) are not changed. Again, this is a political issue, and societies, especially democratic societies, have demonstrated time after time that these problems can be worked out—maybe not to everyone's satisfaction or without some pain, but nonetheless worked out.

10.4.2 Long life may modify our perception of personal achievement and a progressive society

Many view the prospect of a long life and extended youth with great optimism and see it as a possibility for new opportunities. With the expectation of a longer life, individuals are more likely to engage in projects or new ventures that are beyond reach in a shorter life that requires a more careful prioritizing of goals. Mistakes may simply encourage a person to choose a new career that fits more closely with his or her personality and aspirations. Such a move could easily be undertaken at age 70 or 80, if you have the prospect of living another 30 –40 years. The expectation of a 120-year healthy life span may mean the young will be more willing to experiment with risky vocations and avocations, knowing they will have time to try again with the same venture or start a new one. Since risk is the cornerstone of discovery and progress, society will be the beneficiary here.

Other bioethicists take a more pessimistic view of what healthy longer lives might mean for personal achievement. They theorize that an extended youth could remove a sense of urgency and result in a decreased commitment to goals and aspirations. If you knew you had the chance for a “redo,” you might be less inclined to be totally committed to any particular venture. The stick-to-it attitude would give way to prematurely abandoning one's ventures. The redo then becomes the way of life. Goals, aspirations, and the value of personal achievement, as we know them today, could simply lose their meaning, leading us to become a society of the status quo rather than a progressive society, as has historically been the case.

10.4.3 Extended 寿命 may change our responsibility for renewal of the species

An extended life span could also disrupt individuals' sense of responsibility for renewing the species. Proponents of this position point to the fact that the increase in life span during the twentieth century was accompanied by a decrease in birth rate and the trend toward starting reproduction later in life. The sense of urgency about having children is being replaced by the feeling that it can wait—there's plenty of time, later, to enjoy a more stable family life; youth should be spent living the “good life.” However, many couples find that the “good life,” without the responsibilities of children, is too difficult to give up, and so they fail to reproduce at all. In addition, those delaying reproduction may find that, later in their reproductive life span, the will to have babies now exists but the physiology of the reproductive system does not cooperate. Both men and women become less fertile as they approach the end of their reproductive period. Moreover, for women, the increase in birth defects after the age of 35 may seem too great a risk to consider having babies. A reduction in the birth rate will simply reflect biology.

Others believe that birth rate has little to do with life span. Rather, birth rates are more tied to the economic prosperity that comes with the shift from agrarian to industrial societies; longer lives are simply one of many positive outcomes of the industrial society. In an agrarian society, much like all societies before the start of the twentieth century, children are viewed as an asset because they add value to the family by providing labor for work on the land. Children in industrial societies are dependents, costing the family resources. Historically, agrarian societies could expect one in four of their children to die before reaching the age of reproduction, so couples often had many children as a hedge against the loss of labor. Today, in the developed countries, it is the rare couple that loses a child to disease or accident. Life in an industrial society, together with the gains in health care for children, means that couples have fewer children.

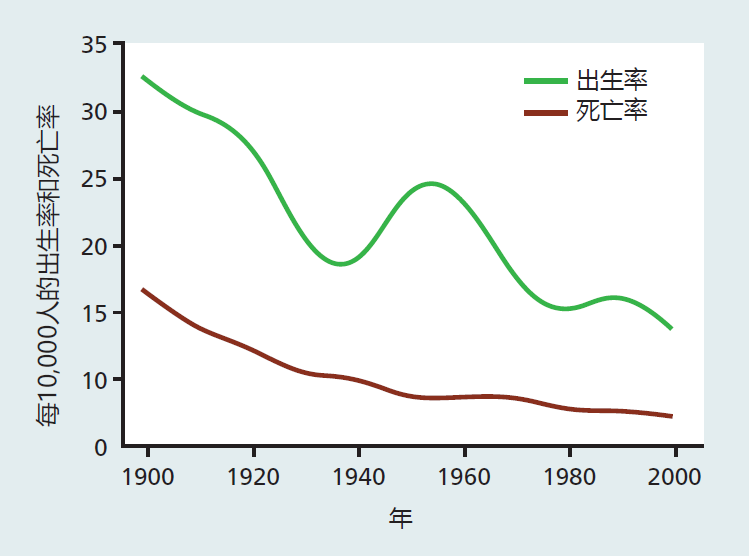

The declining birth rate in the twenty-first century may simply reflect the natural evolution of populations living in environmentally stable conditions, rather than a decreased desire to renew the species. As you learned in Chapter 3, the number of live births is significantly lower for populations living in environmentally stable conditions than for populations with more variable environmental conditions. Most economically developed countries are characterized by a vast majority of the population having sufficient food, housing, clothing, health care, and other basic needs of life—that is, a stable environment. There is no need to add children to the family as insurance to offset future losses of family members due to environmental hazards. Such a society becomes stable, with birth rates approaching death rates (Figure 10.10). The stability of this population will most likely continue, even with extended youth and longevity.

Figure 10.10 Birth and death rates in the United States, 1900–2000. (Death rates from Department of Health and Human Services, National Center for Health Statistics, Natl Vital Stat. Rep. 54(20), Aug. 21, 2007. Birth rates from U.S. National Center for Health Statistics, U.S. Public Health Service, Vital Statistics of the United States, Vols. I and II, 1971–2001.)

The issue of reproductive abilities in individuals with extended youth and life span is also controversial. As you have learned throughout this text, reproduction and longevity are tightly coupled. A change in longevity implies a change in reproductive ability and reproductive life span. This is all the more possible given that extended youth and a longer life will most likely be the result of interventions taking place early in life, during development (see Chapters 3 and 5). In addition, solutions to the problems of decreased fertility and birth defects are being investigated much more vigorously than ways of extending the life span. One can expect advances in reproductive medicine to at least parallel advances in other areas of health.

10.4.4 Low birth rates and extended 寿命 may alter the current life cycle of generations

The structure of families and society is established around a life cycle in which each generation expects to play a well-defined role. For most of history, and for modern society, the life cycle of the family has included three generations: children, parents, and grandparents. Children, the new generation, are nurtured into adulthood by relatively young parents. Parents are expected to be the primary caregivers and to teach this new generation the basic tools needed for an independent adult life. Grandparents often are more or less extraneous to the caregiving for the new generation, playing only a supporting role in the needs of their grandchildren—babysitting, providing gifts, and so on. The important role of grandparents in the family structure centers more on imparting the wisdom of a lifetime of experience to their children, the parents of the new generation. The path for transfer of knowledge and wisdom in this three-generation life cycle, grandparents to parents to children, is short enough that family traditions are passed on without significant alteration. The family gains its own identity, and the individuals within the family feel a sense of belonging.

The three-generation structure of the family can be used as a metaphor for society in general, with each generation having a particular role. The new generation of children is expected to participate in a training and education system that prepares them for their eventual role as productive citizens of society—similar to the parent-child relationship. On the transition from training to work and inclusion as adult members of society, individuals must take their place at the bottom of the ladder and learn the “ways of the world.” As in the grandparents' role in the family structure, the ways of the world are imparted by the older generation at the top of the ladder, those who have been through the process themselves. The three-generation structure of society also provides the individual with incentives to achieve and to move society forward in a positive direction. We learn early on that success in school will lead to success at work and in the community, which will lead to authority, power, and wealth.

The three-generation life cycle in the family and in society has developed based on a 60- to 80-year life span. In this model, the child can expect to progress to the parent, and the parent can expect to progress to the grandparent. The expected and orderly progression occurs because the grandparent or older generation is removed by death or infirmity, leaving room at the “top.” But what if extended youth and a longer life delay death and infirmity so that the “wisdom” positions in the family and in the top tiers of society become overcrowded? Imagine, for example, a family structure in a world where average life span is 120 years. The family of today, children, parents, and grandparent, will give way to a family that includes healthy and active great-grandparents, great great-grandparents, and possibly great-great-great-grandparents. Thus, the wisdom position in the family grows from 4 grandparents to as many as 32 great-great-great-grandparents. The succession of family tradition and identity made possible by the three-generation model weakens due to the sheer bulk of input from the wisdom positions. There are those that suggest the loss of family identity will lead to the loss of individuals' connection to the past and will challenge individuals' view of their own place in the world.

Some predict that as birth and death rates approach equilibrium (see Figure 10.10)— a trend that will undoubtedly continue in a society having a large and healthy older population—total population size will stagnate, economic growth will become sluggish, and job creation will slow down. Moreover, with the extended youth and health of the older population, fewer people in top-tier jobs or with seniority will be likely to retire. A reduction in jobs at the top means slower advancement for those on the way up and a shortage of jobs for the younger generation moving from training to work. Our concept of hard work leading to success will be challenged. Given all this, we will need to redefine what constitutes a productive member of society. Many experts suggest that this redefinition will be slow and will take a considerable toll on the first generation to deal with this new economic structure.